After the Revolutionary War, the United States found itself dependent on the goodwill of the American Indians. The survival of the young nation hinged on establishing and maintaining peace. With no standing army of consequence, securing the allegiance of the native tribes away from their former European allies became an essential part of the country’s foreign policy.

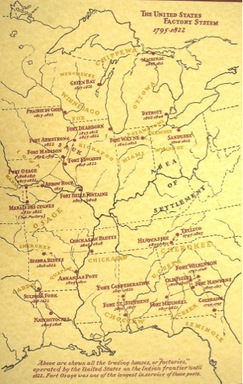

The fur trade was the primary avenue for maintenance of these alliances. As a British colonial officer, George Washington observed first hand the success (and failures) of the British trade system. Washington concluded that if the Indian nations were to be retained as American allies and kept at peace, a successful system regulating the fur trade had to be established. As President of the United States, he quickly moved to establish the American factory system as a vehicle to secure the allegiance of the Native Americans. In 1796 Congress appointed funds to establish widespread trade with the Indians at special sites where government-owned trade goods, handled by government appointed “factors” would win the loyalty of the various Native American tribes.

The reports of Meriwether Lewis and William Clark on their journey into the Northwest convinced President Thomas Jefferson of the value of the fur trade in securing America’s national interests. Attributing Indian unrest to Americans and foreign private traders, Jefferson extended the scope of the factory system, making it a key diplomatic and economic weapon for protecting American interests in the western territories. Jefferson’s motive was purely political. As he wrote to Meriwether Lewis, “Commerce is the great engine by which we are to coerce them [the Indians], and not war.” John Mason in a letter to George Sibley, put the intent of the factory system more subtly, “…the principal object of the government in these establishments being to secure the friendship of the Indians in our country in a way most beneficial to them and the most effectual and economic to the United States.”

The factory system was never intended to make a profit; policy dictated sound fiscal management to effectively cover expenses. Above all, the system was to win the good will of the Native Americans and to secure their economic dependence on American trade goods. The instructions for operating procedures were very explicit and designed to promote uniformity in Indian policy. They impressed on government agents (factors) the importance of “proper conduct” in dealing with their “charges.” As Mason instructed, factors were to, “…avail yourself of every proper means and opportunity of impressing these people favorably to the United States government.” As ambassadors of the United States all actions, all transactions of the factors and their personnel were to be guided by this principle: impress these nations with honor, integrity and good faith of the government.

No damaged or inferior goods were to be passed off to the Indians without full disclosure and allowances (discounts) being made. Demeanor was to indicate respect, friendship and the desire to maintain a solid relationship. At the same time factors were to constantly demonstrate the power of the government. Since the Native Americans viewed anyone they could easily take advantage of as stupid and weak, it was important for factors to display a very strict and assertive attitude. Government instructions stipulated that, “All attempts on their part at fraud, trick or deception should be discountenanced and prevented if possible…” while also insuring the dignity of the guilty party. Reproof was to be offered in “…the most instructive…” manner possible.

Mason’s final instructions reflect the crucial need to secure loyalty of the Native Americans and use them as buffers between the United States and hostile European based powers. Factors were to be “…conciliatory in all your intercourse with the Indians and so demean yourself toward them generally and toward their chiefs in particular as to obtain and preserve their friendship and to secure their attachment to the United States.”